Pre and Post-Snap RPO

June 26, 2023

Throughout my life, I have experienced many different types of offensive schemes. All were effective in their own right respectively. Growing up as the son of a coach, you learn X’s and O’s early. During my childhood, I sat through plenty of offensive staff meetings and endless quarterback meetings. My father, Bobby Lamb, spent 25-plus years running the Pro-I offense at Furman University, where there was not an RPO to be found. Every defense was lining up in 4-3 quarters and playing ball. Furman would oil up the iso (RT 42 Draw) and play action (RT 27 Boot 299). My first taste of an offensive scheme consisted of seven-step drops and throwing deep digs or lead options with the late downfield pitch.

When I played in high school, the coaching staff watched the Tony Franklin DVDs religiously. Everyone is familiar with that system: 10 personnel, drop-back pass, quick game, and plethora of screens. Two of my high school coaches were my uncles, head coach Hal Lamb and offensive coordinator, Michael Davis. Our RPOs consisted of pre-snap smoke screens and bubbles, hardly anything significant. After I committed to play at Appalachian State, I was extremely excited to play in the offense that I watched torch my father’s Furman teams. Yet perhaps it was quarterbacks like Armanti Edwards and Richie Williams that made that offense so electric.

While at Appalachian State, my football mind flourished. My understanding of the game really developed on the mountain under then-head coach Scott Satterfield. Our offense began as a simple approach with multiple-run schemes. Still, RPOs were an afterthought. We ran inside zone, wide zone, pin and pull, and power read. Pass game-wise, we dabbled in all the basic drop-back passes, quick game, and play-action passes.

After transitioning to the FBS ranks and starting the 2014 season with a 1-5 record, we made some changes before we played at Troy. Our staff wanted to simplify the run game to give us better opportunities against bigger and stronger defensive linemen. We bought into zone schemes only. This allowed us to master the wide zone and get those gaps moving laterally, which in turn translated to running the ball far more effectively. We beat Troy and won the next five games that season to kickstart the Satterfield era at Appalachian State.

Our Appalachian offense evolved into a pistol, run-first offense. The wide zone was our main run, followed by tight zone. Hard sell play-action was the bulk of our pass game and RPO was essentially a cuss word to our then-offensive line coach, Dwayne Ledford. Recruit well at running back, find your numbers, and run on the extra hat or hats. For the most part, that was the game plan. Instead of having a post-Snap RPO to control the extra hat, Satterfield used a ton of speed motion to control the back end and cause confusion with run fits. Our version of RPOs turned into triple-option concepts off the pistol tight zone and orbit motions. The triple-option look out of pistol and the pistol wide zone blended well and completed our run game.

My love for running the football and doing so dominantly started at Appalachian State. As a player in this system, I enjoyed learning all the details on the wide zone and the different ways to defend it. After my playing career, I transitioned into coaching and started as a graduate assistant at the University of South Carolina, where I worked under then-offensive coordinator Bryan McClendon and quarterbacks coach Dan Werner. This is where I got my first glimpse of true post-snap RPOs. I remember watching Werner’s clips of when he was the offensive coordinator at Mississippi, where he had Chad Kelly. Kelly rode the wave on the mesh and absolutely ripped the football to open grass with a quick trigger. At South Carolina, we took care of that seventh man with a ride-and-decide RPO, using five-step glances behind the free safeties who filled the alley and controlled the nickel with five-step beaters and hitches. During my two years in Columbia, I really started to understand how to set up RPOs and make it as easy as possible on the quarterback.

In 2020, I took that knowledge to Gardner-Webb, where I became the offensive coordinator/quarterbacks coach. There, we had a lot of success offensively with our RPO philosophy. At Gardner-Webb, it is a struggle to dominate the line of scrimmage offensively. So to put our team in the best position to score points, RPOs gave us the best opportunities. We trusted our quarterbacks’ decision-making and ball-handling skills. Also, we were explosive at the skill position. This resulted in a successful RPO game with a ton of catch and runs. Although I am now the quarterbacks coach at Virginia, I will explore our pre- and post-snap RPO philosophy while at Gardner-Webb in this essay.

RPOs within a Game Plan

My heart will always be with the wide zone and running the football. I love giving the guys upfront the confidence to line up and run the rock. You also must take advantage of nosey hats and bad eyes in the back end. I believe in blending both of those dynamics in moderation. Within a game plan, I like to have a set number of RPO runs and another set of guaranteed runs. This aids in the separation of the two categories and helps the play-caller control the game at his own pace.

When developing the game plan, we like to have the quarterback involved as much as possible. After all, he is the one pulling the trigger and making the decisions. The quarterback needs to completely understand all the RPOs on the final call sheet. What type of RPO is it? Who are we keying? Where are our eyes? As coaches, we know when calling an RPO, there will be some “ifs” after the play. There are give-and-takes when calling RPOs. The quarterback’s read could be to pull and throw, but the running back would have scored a touchdown IF the ball were handed off. Instead, we have a 10-yard completion and a first down. As coaches, we must trust the quarterback to “win the down”.

Types of RPOs

For teaching purposes, I personally like to break down RPOs into categories: pre-snap RPOs and post-snap RPOs. From my experience, this helps the quarterback’s understanding of our intentions on each RPO. Most of these designed RPOs will have both types of reads built in, pre-snap and post-snap.

Pre-Snap

On pre-snap RPOs, the quarterback’s decision is made before he ever receives the football. We preach to our guys to never catch the rock blank. It is an awful feeling as a quarterback to take the snap and the next thought is, what now? Our pre-snap and post-snap process is for another discussion, but we want our guys to have a pre-snap plan and a post-snap decision on every single play. In this case, the decision is already made within the quarterback’s pre-snap plan. Mechanically, on all these pre-snap RPOs, we don’t want to ride the mesh point. We refer to the mesh as riding the wave. If the decision is made before the snap is taken, there is no reason to ride the wave before throwing the pre-snap RPO. I teach pre-snap RPOs as two different reads: a numbers read and a free-access read.

Numbers

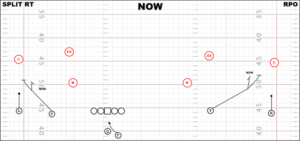

These consist of perimeter, quick screens that are tagged onto runs. Nearly every offense in the country utilizes these types of RPOs. All of these perimeter RPOs have players blocking for the ball carrier. By design, we can have one to three players blocking on these perimeter RPOs. When running these perimeter screens, most teams are reading a certain defender. For us, we want to use a number count. That is because defenses in today’s game are so diverse in their pre-snap looks and post-snap schemes. We choose to broaden the teaching and simplify the learning. If we have two players blocking for the perimeter screen, our quarterback is looking for No. 3. Where is No. 3 coming from? What is his body language to the football? Can I beat No. 3 with the ball and gain five yards? The following are some examples of a pre-snap RPO with a numbers read.

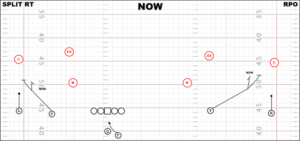

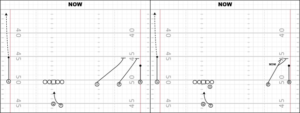

We called the aforementioned a smoke screen, “Now.” Now is mirrored on both sides unless you are the single receiver, then you have a hitch/win. We have different rules for the now route based off the corner leverage.

-If the corner is off (six-plus yards), run a three-step now route.

-If the corner is a hard corner (within five yards), shorten your now route to one step.

-If the corner is pressed, run a three-step tunnel route rubbing shoulders with your blocker.

We teach the quarterback to simply see the structure and beat the numbers. In the top diagram, we only have one player blocker for the now route. Where is No. 2 coming from? Can I beat No. 2? The No. 2 can change with the structure. So, the quarterback must determine where the No. 2 is coming from and if we can gain 5 yards throwing it out there. When in doubt, hand it off. We usually run “Now” with wide splits to clean up the box for the quarterback and offensive linemen.

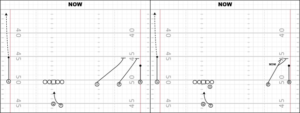

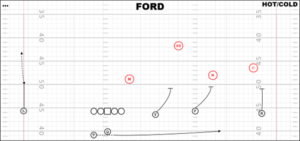

The above pre-snap RPO was our flare screen. In this diagram, we had a quarterback draw paired with it. We can get to this in a multitude of ways. You would see us send an orbit motion behind the quarterback for the flare with a run working in the other direction. In this diagram, we have three players blocking the three most dangerous the path of the ball carrier.

With this structure, the R will block No. 1 (cornerback), the F will block No. 2 (nickel), and the Y will block No. 3 (Mike or free safety). The good thing about how we teach this is that the read stays the same no matter how we design it. In this example, we would ask our quarterback to see the structure and find No. 4. If the Mike flies out with the running back motion and the strong safety stays high, we are still good. The strong safety would be considered No. 4 and we will run on him with a 10-yard cushion. A lot of scenarios can arise, so we simply tell our guys to find the extra number instead of keying a certain defender. That way we are covered in all the diverse looks from the defensive side of the ball.

Another pre-snap RPO in which our decision is based on numbers is the bubble. Every team has some type of bubble in their playbook. We would read the bubble as a number count RPO. We had tremendous success with the condensed bunch bubbles at Gardner-Webb. The No. 1 receiver is running the bubble. The point man is fighting for the outside pad of the most dangerous defender. The No. 3 receiver is switch releasing off the point man and blocking the No. 1 defender to the sideline, which is usually the corner. Nothing, however, changes for the quarterback, who will find No. 3. It could be a rolled-down strong safety or a wide backer. The quarterback should take this play to the next level and understand because of the condensed formation that he must let the bubble develop. Even though the quarterback knows he wants to throw it pre-snap, he can give the running back a quick show-and-go.

Free Access

The next example of the pre-snap RPO is the free-access throw. For us, the free-access throw showed up in almost every RPO design we had. Either it is a single quick route backside of a run or it is built into a downfield RPO to give us another opportunity for a completion. For example, in the flare diagram above, we have a single hitch/win-backside. The quarterback will know where the free access throws are in all our RPO concepts. I always preach to our quarterbacks that we never turn down free yards, but we better be sure those yards are free. To know if the yards are free or not, we study the leverage and structure of the defense to the side of the free-access throw. If we have a free access hitch/win and our corner is squatted at five yards and the safety has the potential to get over the top, those yards are not free! If we get a corner with off and inside leverage and no threat of a safety over the top, let’s definitely take those free yards.

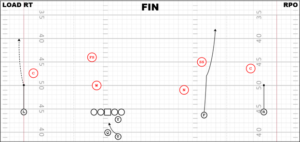

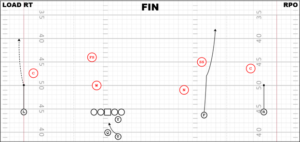

When taking free-access throws, there is no need to start the mesh mechanics, because it turns into a quick game for us. Catch the snap, avoid the running back depending on the run call, and deliver the ball. The next step in this process is to understand the timing of the deeper free-access throws. In the diagram below, we have our RPO called “Fin.” Fin is built with three free-access throws: a hitch/win by the single, an inside fade by the slot, and a locked hitch by No. 1.

All the routes in fin are free access to the quarterback and the decision is made to throw these before the ball is snapped.

If we have off corners with a good structure, we can take the free-access hitches. If we have man coverage and a good matchup in the slot, we can take that inside fade. With these downfield free-access throws, we need to ride the wave of the mesh. This is the next step in understanding the free-access RPOs. The mesh gives time to the quarterback. If we do not mesh, the defensive line will convert to pass rush while the blockers are in run mode, which is hardly ideal. Therefore, we create that mesh to help the offensive line keep those defensive linemen in run fits a couple seconds longer. It is the same philosophy if we wanted to take a free-access hitch/win vs. press man. The hitch is converting into a win route or in other terms, a quick fade. It is very important for the quarterback to understand the entire picture and process.

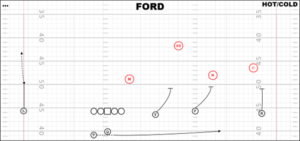

Post-Snap – Grass Reads

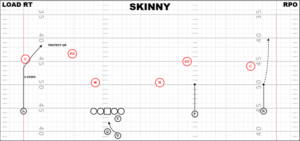

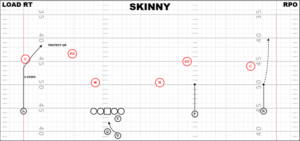

Post-snap RPOs are traditional “ride and decide” designs. Most of our designs have one route which is the post-snap read and everything else is pre-snap. The “Skinny” diagram below is a great, simple example of our post-snap RPOs. In the skinny concept, the hitches are pre-snap

free-access throws and the skinny is the post-snap decision. The coaching point for throwing any post-snap RPO is to see the structure, ride the wave, and read the grass.

I am aware that some coaches teach downfield RPOs as reading the plus-one defender or the key defender. Again, defenses today are diverse and multiple. We want to put the quarterback in the best position to be successful without overloading them with information. Don’t get me wrong, our quarterback needs to know who the unblocked defender is in all the schemes and designs.

But in some of our designs, we won’t attack the extra hat adding to the box, and will instead attack the grass and space. Instead of giving our quarterback one defender to key, we call it a “grass read.” For example, let’s look at the skinny diagram below and pretend that the free safety is the extra hat who is adding to the box. Obviously, if he rolls down and gets nosey on the mesh, we throw it off his ear to the skinny. He also can roll to the middle of the field or be a Cover 2 safety over a trap corner. In both those situations, the free safety is not adding to the box, but is vacating the grass for the skinny route. We have just found it more useful to teach grass reads instead of keying a defender adding to the box.

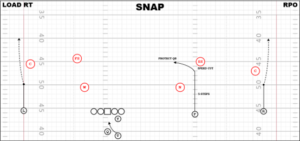

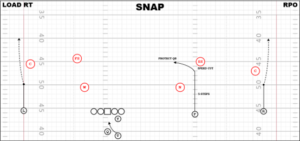

The diagram below was one of our core RPOs. We called it “Snap”. In this 2X1 look, the two outside receivers have hitch/wins and the inside slot has a snap route, which is a five-step speed-in. Most important for that snap route is to close that back shoulder and be friendly to the quarterback. For teaching purposes, the hitches are free-access throws, and the snap route is the post-snap look. Again, we call it a “grass read.” We view the pre-snap structure, ride the wave, and read the grass. This broadens the read and allows us to be successful vs. these multiple defenses. We also can “back read” downfield RPOs. We have designed the run so that we are meshing with our back to the post-snap RPO. It gives the defense a different look and can slow down defenders on the front side of the run.

In conclusion, the aforementioned diagrams were our main RPOs at Gardner-Webb. Our pre-snap RPOs, which consisted of free-access throws and number counts, and our post-snap grass reads helped our quarterbacks be decisive in the run-pass option game. It allowed them to play fast and with confidence. As a player, I spent my career thinking that RPOs were bad for the soul. However, my coaching journey has allowed my mind to evolve and comprehend how RPOs are incorporated into today’s game. These days, it is hard to turn down the free yards!

For more information about the AFCA, visit www.AFCA.com. For more interesting articles, check out The Insider and subscribe to our weekly email.

If you are interested in more in-depth articles and videos, please become an AFCA member. You can find out more information about membership and specific member benefits on the AFCA Membership Overview page. If you are ready to join, please fill out the AFCA Membership Application.

« « Previous PostNext Post » »

Throughout my life, I have experienced many different types of offensive schemes. All were effective in their own right respectively. Growing up as the son of a coach, you learn X’s and O’s early. During my childhood, I sat through plenty of offensive staff meetings and endless quarterback meetings. My father, Bobby Lamb, spent 25-plus years running the Pro-I offense at Furman University, where there was not an RPO to be found. Every defense was lining up in 4-3 quarters and playing ball. Furman would oil up the iso (RT 42 Draw) and play action (RT 27 Boot 299). My first taste of an offensive scheme consisted of seven-step drops and throwing deep digs or lead options with the late downfield pitch.

When I played in high school, the coaching staff watched the Tony Franklin DVDs religiously. Everyone is familiar with that system: 10 personnel, drop-back pass, quick game, and plethora of screens. Two of my high school coaches were my uncles, head coach Hal Lamb and offensive coordinator, Michael Davis. Our RPOs consisted of pre-snap smoke screens and bubbles, hardly anything significant. After I committed to play at Appalachian State, I was extremely excited to play in the offense that I watched torch my father’s Furman teams. Yet perhaps it was quarterbacks like Armanti Edwards and Richie Williams that made that offense so electric.

While at Appalachian State, my football mind flourished. My understanding of the game really developed on the mountain under then-head coach Scott Satterfield. Our offense began as a simple approach with multiple-run schemes. Still, RPOs were an afterthought. We ran inside zone, wide zone, pin and pull, and power read. Pass game-wise, we dabbled in all the basic drop-back passes, quick game, and play-action passes.

After transitioning to the FBS ranks and starting the 2014 season with a 1-5 record, we made some changes before we played at Troy. Our staff wanted to simplify the run game to give us better opportunities against bigger and stronger defensive linemen. We bought into zone schemes only. This allowed us to master the wide zone and get those gaps moving laterally, which in turn translated to running the ball far more effectively. We beat Troy and won the next five games that season to kickstart the Satterfield era at Appalachian State.

Our Appalachian offense evolved into a pistol, run-first offense. The wide zone was our main run, followed by tight zone. Hard sell play-action was the bulk of our pass game and RPO was essentially a cuss word to our then-offensive line coach, Dwayne Ledford. Recruit well at running back, find your numbers, and run on the extra hat or hats. For the most part, that was the game plan. Instead of having a post-Snap RPO to control the extra hat, Satterfield used a ton of speed motion to control the back end and cause confusion with run fits. Our version of RPOs turned into triple-option concepts off the pistol tight zone and orbit motions. The triple-option look out of pistol and the pistol wide zone blended well and completed our run game.

My love for running the football and doing so dominantly started at Appalachian State. As a player in this system, I enjoyed learning all the details on the wide zone and the different ways to defend it. After my playing career, I transitioned into coaching and started as a graduate assistant at the University of South Carolina, where I worked under then-offensive coordinator Bryan McClendon and quarterbacks coach Dan Werner. This is where I got my first glimpse of true post-snap RPOs. I remember watching Werner’s clips of when he was the offensive coordinator at Mississippi, where he had Chad Kelly. Kelly rode the wave on the mesh and absolutely ripped the football to open grass with a quick trigger. At South Carolina, we took care of that seventh man with a ride-and-decide RPO, using five-step glances behind the free safeties who filled the alley and controlled the nickel with five-step beaters and hitches. During my two years in Columbia, I really started to understand how to set up RPOs and make it as easy as possible on the quarterback.

In 2020, I took that knowledge to Gardner-Webb, where I became the offensive coordinator/quarterbacks coach. There, we had a lot of success offensively with our RPO philosophy. At Gardner-Webb, it is a struggle to dominate the line of scrimmage offensively. So to put our team in the best position to score points, RPOs gave us the best opportunities. We trusted our quarterbacks’ decision-making and ball-handling skills. Also, we were explosive at the skill position. This resulted in a successful RPO game with a ton of catch and runs. Although I am now the quarterbacks coach at Virginia, I will explore our pre- and post-snap RPO philosophy while at Gardner-Webb in this essay.

RPOs within a Game Plan

My heart will always be with the wide zone and running the football. I love giving the guys upfront the confidence to line up and run the rock. You also must take advantage of nosey hats and bad eyes in the back end. I believe in blending both of those dynamics in moderation. Within a game plan, I like to have a set number of RPO runs and another set of guaranteed runs. This aids in the separation of the two categories and helps the play-caller control the game at his own pace.

When developing the game plan, we like to have the quarterback involved as much as possible. After all, he is the one pulling the trigger and making the decisions. The quarterback needs to completely understand all the RPOs on the final call sheet. What type of RPO is it? Who are we keying? Where are our eyes? As coaches, we know when calling an RPO, there will be some “ifs” after the play. There are give-and-takes when calling RPOs. The quarterback’s read could be to pull and throw, but the running back would have scored a touchdown IF the ball were handed off. Instead, we have a 10-yard completion and a first down. As coaches, we must trust the quarterback to “win the down”.

Types of RPOs

For teaching purposes, I personally like to break down RPOs into categories: pre-snap RPOs and post-snap RPOs. From my experience, this helps the quarterback’s understanding of our intentions on each RPO. Most of these designed RPOs will have both types of reads built in, pre-snap and post-snap.

Pre-Snap

On pre-snap RPOs, the quarterback’s decision is made before he ever receives the football. We preach to our guys to never catch the rock blank. It is an awful feeling as a quarterback to take the snap and the next thought is, what now? Our pre-snap and post-snap process is for another discussion, but we want our guys to have a pre-snap plan and a post-snap decision on every single play. In this case, the decision is already made within the quarterback’s pre-snap plan. Mechanically, on all these pre-snap RPOs, we don’t want to ride the mesh point. We refer to the mesh as riding the wave. If the decision is made before the snap is taken, there is no reason to ride the wave before throwing the pre-snap RPO. I teach pre-snap RPOs as two different reads: a numbers read and a free-access read.

Numbers

These consist of perimeter, quick screens that are tagged onto runs. Nearly every offense in the country utilizes these types of RPOs. All of these perimeter RPOs have players blocking for the ball carrier. By design, we can have one to three players blocking on these perimeter RPOs. When running these perimeter screens, most teams are reading a certain defender. For us, we want to use a number count. That is because defenses in today’s game are so diverse in their pre-snap looks and post-snap schemes. We choose to broaden the teaching and simplify the learning. If we have two players blocking for the perimeter screen, our quarterback is looking for No. 3. Where is No. 3 coming from? What is his body language to the football? Can I beat No. 3 with the ball and gain five yards? The following are some examples of a pre-snap RPO with a numbers read.

We called the aforementioned a smoke screen, “Now.” Now is mirrored on both sides unless you are the single receiver, then you have a hitch/win. We have different rules for the now route based off the corner leverage.

-If the corner is off (six-plus yards), run a three-step now route.

-If the corner is a hard corner (within five yards), shorten your now route to one step.

-If the corner is pressed, run a three-step tunnel route rubbing shoulders with your blocker.

We teach the quarterback to simply see the structure and beat the numbers. In the top diagram, we only have one player blocker for the now route. Where is No. 2 coming from? Can I beat No. 2? The No. 2 can change with the structure. So, the quarterback must determine where the No. 2 is coming from and if we can gain 5 yards throwing it out there. When in doubt, hand it off. We usually run “Now” with wide splits to clean up the box for the quarterback and offensive linemen.

The above pre-snap RPO was our flare screen. In this diagram, we had a quarterback draw paired with it. We can get to this in a multitude of ways. You would see us send an orbit motion behind the quarterback for the flare with a run working in the other direction. In this diagram, we have three players blocking the three most dangerous the path of the ball carrier.

With this structure, the R will block No. 1 (cornerback), the F will block No. 2 (nickel), and the Y will block No. 3 (Mike or free safety). The good thing about how we teach this is that the read stays the same no matter how we design it. In this example, we would ask our quarterback to see the structure and find No. 4. If the Mike flies out with the running back motion and the strong safety stays high, we are still good. The strong safety would be considered No. 4 and we will run on him with a 10-yard cushion. A lot of scenarios can arise, so we simply tell our guys to find the extra number instead of keying a certain defender. That way we are covered in all the diverse looks from the defensive side of the ball.

Another pre-snap RPO in which our decision is based on numbers is the bubble. Every team has some type of bubble in their playbook. We would read the bubble as a number count RPO. We had tremendous success with the condensed bunch bubbles at Gardner-Webb. The No. 1 receiver is running the bubble. The point man is fighting for the outside pad of the most dangerous defender. The No. 3 receiver is switch releasing off the point man and blocking the No. 1 defender to the sideline, which is usually the corner. Nothing, however, changes for the quarterback, who will find No. 3. It could be a rolled-down strong safety or a wide backer. The quarterback should take this play to the next level and understand because of the condensed formation that he must let the bubble develop. Even though the quarterback knows he wants to throw it pre-snap, he can give the running back a quick show-and-go.

Free Access

The next example of the pre-snap RPO is the free-access throw. For us, the free-access throw showed up in almost every RPO design we had. Either it is a single quick route backside of a run or it is built into a downfield RPO to give us another opportunity for a completion. For example, in the flare diagram above, we have a single hitch/win-backside. The quarterback will know where the free access throws are in all our RPO concepts. I always preach to our quarterbacks that we never turn down free yards, but we better be sure those yards are free. To know if the yards are free or not, we study the leverage and structure of the defense to the side of the free-access throw. If we have a free access hitch/win and our corner is squatted at five yards and the safety has the potential to get over the top, those yards are not free! If we get a corner with off and inside leverage and no threat of a safety over the top, let’s definitely take those free yards.

When taking free-access throws, there is no need to start the mesh mechanics, because it turns into a quick game for us. Catch the snap, avoid the running back depending on the run call, and deliver the ball. The next step in this process is to understand the timing of the deeper free-access throws. In the diagram below, we have our RPO called “Fin.” Fin is built with three free-access throws: a hitch/win by the single, an inside fade by the slot, and a locked hitch by No. 1.

All the routes in fin are free access to the quarterback and the decision is made to throw these before the ball is snapped.

If we have off corners with a good structure, we can take the free-access hitches. If we have man coverage and a good matchup in the slot, we can take that inside fade. With these downfield free-access throws, we need to ride the wave of the mesh. This is the next step in understanding the free-access RPOs. The mesh gives time to the quarterback. If we do not mesh, the defensive line will convert to pass rush while the blockers are in run mode, which is hardly ideal. Therefore, we create that mesh to help the offensive line keep those defensive linemen in run fits a couple seconds longer. It is the same philosophy if we wanted to take a free-access hitch/win vs. press man. The hitch is converting into a win route or in other terms, a quick fade. It is very important for the quarterback to understand the entire picture and process.

Post-Snap – Grass Reads

Post-snap RPOs are traditional “ride and decide” designs. Most of our designs have one route which is the post-snap read and everything else is pre-snap. The “Skinny” diagram below is a great, simple example of our post-snap RPOs. In the skinny concept, the hitches are pre-snap

free-access throws and the skinny is the post-snap decision. The coaching point for throwing any post-snap RPO is to see the structure, ride the wave, and read the grass.

I am aware that some coaches teach downfield RPOs as reading the plus-one defender or the key defender. Again, defenses today are diverse and multiple. We want to put the quarterback in the best position to be successful without overloading them with information. Don’t get me wrong, our quarterback needs to know who the unblocked defender is in all the schemes and designs.

But in some of our designs, we won’t attack the extra hat adding to the box, and will instead attack the grass and space. Instead of giving our quarterback one defender to key, we call it a “grass read.” For example, let’s look at the skinny diagram below and pretend that the free safety is the extra hat who is adding to the box. Obviously, if he rolls down and gets nosey on the mesh, we throw it off his ear to the skinny. He also can roll to the middle of the field or be a Cover 2 safety over a trap corner. In both those situations, the free safety is not adding to the box, but is vacating the grass for the skinny route. We have just found it more useful to teach grass reads instead of keying a defender adding to the box.

The diagram below was one of our core RPOs. We called it “Snap”. In this 2X1 look, the two outside receivers have hitch/wins and the inside slot has a snap route, which is a five-step speed-in. Most important for that snap route is to close that back shoulder and be friendly to the quarterback. For teaching purposes, the hitches are free-access throws, and the snap route is the post-snap look. Again, we call it a “grass read.” We view the pre-snap structure, ride the wave, and read the grass. This broadens the read and allows us to be successful vs. these multiple defenses. We also can “back read” downfield RPOs. We have designed the run so that we are meshing with our back to the post-snap RPO. It gives the defense a different look and can slow down defenders on the front side of the run.

In conclusion, the aforementioned diagrams were our main RPOs at Gardner-Webb. Our pre-snap RPOs, which consisted of free-access throws and number counts, and our post-snap grass reads helped our quarterbacks be decisive in the run-pass option game. It allowed them to play fast and with confidence. As a player, I spent my career thinking that RPOs were bad for the soul. However, my coaching journey has allowed my mind to evolve and comprehend how RPOs are incorporated into today’s game. These days, it is hard to turn down the free yards!

For more information about the AFCA, visit www.AFCA.com. For more interesting articles, check out The Insider and subscribe to our weekly email.

If you are interested in more in-depth articles and videos, please become an AFCA member. You can find out more information about membership and specific member benefits on the AFCA Membership Overview page. If you are ready to join, please fill out the AFCA Membership Application.